Alan Wake 2 was one of very few 10/10s FandomWire gave the incredible mass of releases this year, so when we were given the chance to talk to Petri Alanko, Remedy’s go-to composer for the Remedy Connected Universe, there was no question we wanted to pick his brain and get some insight to what went on with Alan Wake 2, and beyond. There are some interesting answers and two particularly significant snippets that might give insight into the future of Alan Wake.

Some answers have been edited for clarity and spelling, as well as this interview taking place before The Game Awards, in the case of some inconsistencies.

Petri Alanko is a Remedy Man Through and Through

FW: For those unaware, would you be so kind as to explain who you are and what you do?

PA: I’m Petri Alanko, a composer, and a sound designer and quite often I find myself wearing a producer hat, too. Mostly in-game music, but quite a lot of pop music thrown in as well. Usually, the first two become more or less merged together at some point, especially at the beginning of a large project.

FW: How was your approach different when scoring Alan Wake 2 compared to your other Remedy projects, especially the original Alan Wake?

PA: It comes down to the timeline, I guess – when we first started discussing the concept of the music and soundtrack, it was clear right from the start that we couldn’t re-do what we had done with the original first game, or rather, we wouldn’t. I have a strong objection in repeating something all over again, but I also understand the minds of the fans: there has to be familiarity to connect with, there’s no point in alienating just for its sake.

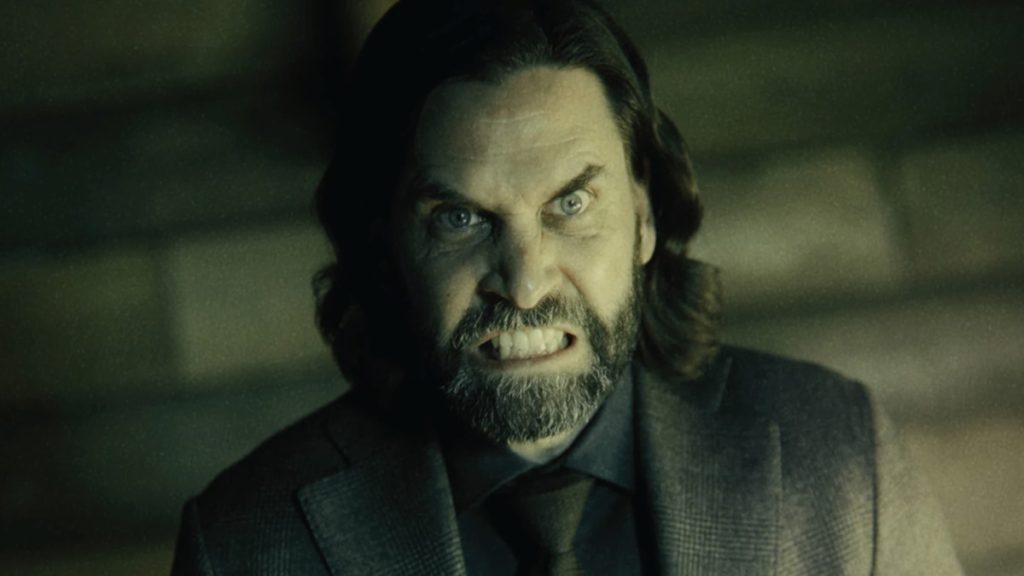

So, in short, I had to take what already existed, but crank it up a few notches to match Alan’s state of mind. After all, he’d been a prisoner in The Dark Place for quite some time, trying to escape, and – in a way – living his Groundhog Day time and again. However, not exactly forget it all every time, due to him leaving clues along the way, searching for an exit. If you encounter that yourself, I’m sure it would affect you after a while, which is what probably happened to Alan during his 13 years of absence… or should I say “presence in The Dark Place”?

I remember playing a lot of Commodore 64 games back in the day, and Rob Hubbard was the first one I paid attention to. I had a few analog monosynths and a polyphonic one already, and his stuff was the first to raise my eyebrows. Martin Galway was another, then came the console era and PlayStation 1, and both Tomb Raider and the original Rayman were my favorites…

Alan could not have a similar sonic world he had in the original game, and I felt compelled to emphasize the horror aspect – we were, after all, making a survival horror game – so his world of mayhem and nightmares had to be as dark and as haunting as one could imagine, lots of sounds being mangled beyond recognition, although they all had a real-world origin and so on; It’s all due to The Dark Place being sort of underwater, remember Alan diving into Cauldron Lake in the original game to release his beloved wife, Alice? That’s his wet tomb.

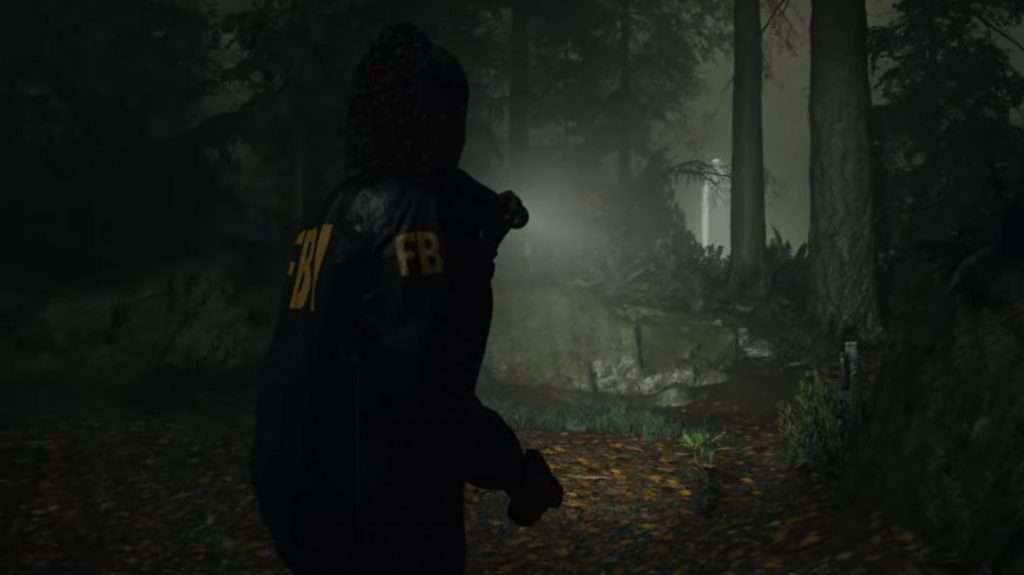

Luckily we were, after all, able to bring in the much more somber tones as well, as Saga is introduced as the other protagonist, and for her, the initial events of the game are much alike Alan’s (compared to the first game) in nature: she’s just visiting some town with her colleague, and they just happen to investigate a ritual serial murder. With two protagonists, I felt it was possible to both continue the story as well as start it all over again. It was a very, clever move from Remedy. Alan Wake 2 can be played despite not having played the original game.

FW: What’s the most challenging aspect of composing for a video game compared to other mediums?

PA: The dynamic nature of the music required is easily the most challenging! I can read the picture and the events, but it’s not even near enough, as one has to remember there are dynamic in-game events, and each player approaches their playstyle differently, some people go straight into the action, whereas someone else may try their best to avoid all crisis, and then there are people such as me who just turn every stone and open every box to learn everything – so there are dozens of spots requiring content, and the more lore the gamer exposes and enjoys, the more the story deepens.

And I haven’t even mentioned the combat scenes, which are totally another matter – luckily I had a brilliant guy helping me out there, Kilian Oser. I definitely want to mention him, as he took a serious burden off my back towards the busiest section of the development, where I had about a hundred cinematics on my desk.

Maybe I should mention “the sheer size of any project nowadays” as a challenge, too? It indeed creates a little head-scratching, as the schedules tend to go tight in the last phase. Quality assurance, playability, bug honing, content additions, some edits here and there, cinematics being edited just enough so that the timing goes bonkers and so on… but, I wouldn’t be in this business if I didn’t love it all.

That’s where you see the game taking its final shape, and sometimes just the look of the graphics took gigantic leaps forward overnight. I don’t mind about the deadlines, at all, as it never lasts long, and if things are planned well beforehand, I mean right from the start, it’s all about scaling your output and workflow to adjust yourself to the pace of the rest of the development.

Okay, having said that, another challenge could be “whether you can handle the pressure or not”. I’ve had my fair share of gigging in the past – I still play live with a band at festivals in front of large audiences – so facing the pressure is a very old friend of mine. If something could happen to antique synths between the soundcheck and the gig itself, it would happen…

FW: Who are your idols and biggest inspirations, and who or what started you on this path?

PA: In-game music, I remember playing a lot of Commodore 64 games back in the day, and Rob Hubbard was the first one I paid attention to. I had a few analog monosynths and a polyphonic one already, and his stuff was the first to raise my eyebrows. Martin Galway was another, then came the console era and PlayStation 1, and both Tomb Raider and the original Rayman were my favorites – and actually, with PS1, I actually started thinking “okay this could indeed be a source of work at some point”, but back then Finland was still in its gaming cradle.

I had played Max Payne 2 and felt it was really captivating, and I started filling in the blanks in my head – the soundtrack was rather sparse back then.

We were, at best, a cell phone country for a while, thanks to Nokia men wearing shoulder-padded style-less suits. The gaming era came a little later, which is when I really felt compelled to have my shoe in the doorway. I had some luck with it, but also had continuously worked to make a move away from “the usual pop music environment”.

Nowadays, I’m very, very fond of my colleague’s works, they each seem to have a style of their own – I hope I have one, too – and I think I should mention Joris de Man, The Flight, Will Roget, Olivier Deriviere and Jack Wall. Each mentioned is someone I would like to work with, such great composers! To be honest, there are loads and loads of others, too, but I just booted up Spotify and looked at my playlist.

Movie music is totally another thing – it doesn’t differ in production values at all, instead, it’s only “linear” compared to game music’s “dynamic” nature, meaning the movie scenes stay put forever. If I’m driving, I usually listen to movie soundtracks – and in most cases I try to listen to the music before I see the movie, just to sort of check whether the composers are able to plant the scenes into my brain like a proper mentalist could. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it feels strangely off, as if the editor and the director have made last-minute edit changes.

Production-wise there seems to be one name who turned my heart around quite a few times when I was a teenager and in my early adulthood: Alan Wilder. His work with Depeche Mode and Recoil is something that resonates in my head, and I seriously would like to do something along these lines for some soundtrack, at some point. Okay, him, Ryuichi Sakamoto and Trent Reznor, but Mr. Wilder kicked my head first.

FW: What drew you towards wanting to compose for Remedy and other video game developers/properties?

PA: Actually, it was Remedy only. I had no will or wants to work with others, only with Remedy. I’ve done projects for other companies after the original Alan Wake, but back in the day, I felt it was either them or nobody. Luckily our common friend introduced me to Remedy’s people and somehow I was invited to do “something” for “one of their ideas”.

After having been around with Remedy since August 2004 more or less, which is when I did the first track, a demo (although I didn’t know it was a demo, I was just happy to do something they paid for), I’ve seen them turn into a massively creative production house. In essence, nothing has changed from the start: they still believe in the highest possible production values as well as the importance of a story – and also the backstory, which is what some developers tend to forget.

There’s never only ‘right now’ with Remedy, there’s always a background for each character and event, and that’s where the story points are anchored, and that’s what makes their stories both believable and easy to write.

I had played Max Payne 2 and felt it was really captivating, and I started filling in the blanks in my head – the soundtrack was rather sparse back then. However, still it had ‘that Remedy vibe’ to it, and I knew the composers, now even personally, which is not unusual, remembering the Finnish music professional headcount…

I feel I hear music every time I see a picture or a cinematic, that’s something I cannot escape or silence. There’s music in there, and it needs to come out. Sometimes, as it is with Remedy, a theme just appears in my head, and I hear it as if it was already produced and mastered. The actual physical job remains, however, how to turn my brain image into a listenable product? I tend to think more than sit in front of the workstations, I want to be sure about what’s playing in my head before doing a thing.

Sometimes the theme I hear is left for weeks before I lay in anything – I have this philosophy where I follow the dogma “If it’s good enough, you remember it without writing it down”. That happened with Alan Wake 1, Quantum Break, Control, Alan Wake 2, and everything in between. I also follow that rule with my pop songwriting. If it sticks, there’s a good reason for it.

Alan Wake would be a perfect ground for a TV show, but whether others see it that way, I don’t really know. A lot of interest has been around, and I must add I have no idea whatsoever of what is going on – it’s not my thing to know or take care of.

I’m attracted to aesthetics and the overall quality. How people behave, talk, tell stories, and so on – it tells a lot about the company and their IP or the products, how they value their employees, how the company values form et cetera. I’ve said “no thank you” a few times, sometimes I don’t even know why and the actual reasons dawned on me later – as I’m keen on following my intuition, it has never let me down.

Sometimes it’s about a talk – with Remedy, I enjoy the talks with Sam Lake and others, I feel they’re my fuel, the people and their stories, and this applies also to the imaginary game characters. That sounds weird, but what I mean is it’s important that there’s more than only “now” for a game character. They should have a past and a future – a life, in other words.

FW: What makes a great score in your opinion?

PA: It has to work on its own. It’s good if it brings value to the main product and even better if it carries the emotions forward – I’ve used the term “music is a vessel for emotions” – but it definitely works best if one can get the feels from it without the game, the main product itself.

I don’t think the production values play the main role, but they help in bringing the concept forward, and I personally am a fan of detailed, classy work. For myself, the best game soundtracks have longevity, they stand the test of time without ever becoming cheesy or overly nostalgic due to technical reasons or limitations. If it works by itself, it indeed is music. If it needs a picture or a game, it’s just a production landfill.

Don’t get me wrong, that is needed too sometimes, and even then it has its place – also in the listeners’ hearts – but the best music draws pictures and takes you to places you haven’t seen… yet. Emotions play a strong role in that, so everything comes down to a performance, a set of brilliant people playing together, or alone. A great score has a soul, it becomes an entity of its own, and it never steals the show from the main product – those two need to be tangled together.

FW: Other than your own work, what would be your favorite video game score/soundtrack?

PA: I loved Yamaoka-san’s original Silent Hill stuff. Totally in another direction are the Horizon Zero game soundtracks, I love those a lot! I’m not really keen on overly large war elephant orchestra rumbles with 140 people blasting sforzandos and then some, I’m more on the subtle and subjective side with my favorites. One that also comes to mind is Alien: Isolation’s score – it owes something to Goldsmith as an homage, but takes its own approach and lives as an entity of its own. A brilliant extension to the Alien universe, so to speak.

FW: At what point of development were you brought on board to compose, and did your score directly change the approach of the narrative or visual designs being implemented?

PA: Actually, I was on board well before the production began, as I wrote the first track already back in 2011… but in general, I’m usually brought in at the conception stage, as it matters a lot: many sound library sessions happen in the beginning and there’s a lot of material to draw from, and being around from the earliest days helps you to immerse yourself in the story, to enjoy its first bites and slaps – I usually write about 10-12 concept tracks that carry the essence of the then overall feeling, or the essence of the concept itself, and I use those to bring me back to that intuition-inspiration-improvise phase I so thoroughly enjoyed, sometimes years before.

I’d say in 95% of cases the music/sound concept doesn’t change, but it evolves and gathers more colors to it. It’s a little like anything else in the game: you need to give it time to let it mature and to cling in, it’s similar with graphics and environments – I hate when some companies react instead of being proactive: plan, don’t react.

Music needs to have its value, you just can’t glue it in at the last minute. If you value your IP and your product (and your team), give music time and space, also in the schedule. It’s not a mandatory expense item, it’s a crucial part of the whole. Like they say in those annoying clips in the Blu-Rays and DVDs: “You wouldn’t use some dodgy 3D characters as a protagonist either, why would you rush with the emotional vessel either?” The same applies to audio in general, I must add.

When it comes to whether my score actually affected any choices… I have no idea, but it seems in a few places some changes were made according to something I wrote, and what was done required no re-do rounds for music, so I’m willing to turn to “maybe music changed something”. I’m sure someone at Remedy knows better, but please, don’t wake me up.

FW: What would be your dream project, whether it would be in film, TV, or video games?

PA: Something connecting both the film/TV and the games. I’d love to expand the concept of a product that way. I know it’s a rare opportunity to do that, but here’s to hoping. I’m not the one who goes knocking on the doors, I’m more of the “they’ll call if they need” school. I literally hate being a creative salesman, I’m not that at all, I’m a specialist, not a generalist.

However – and this is funny – I’m really good at selling others’ services, but when it comes to my own services… oh damn, it’s very revolting and feels just cheap.

I was very pleasantly surprised how The Last Of Us managed to pull it together with music; they kept their essence, and they maintained the concept there, too. Such brilliant work! Oh damn… Santaolalla needs to be mentioned here. I value his works greatly, and if someone hasn’t heard the ‘Liebes Kind’ soundtrack yet (with Juan Luqui), do yourself a favor and take an hour off, have a cuppa joe or tea, and thank me later.

Alan Wake would be a perfect ground for a TV show, but whether others see it that way, I don’t really know. A lot of interest has been around, and I must add I have no idea whatsoever of what is going on – it’s not my thing to know or take care of.

I’d love to compose a post-apocalyptic thriller movie with some romantic flavors – or just blast controls at eleven with some scary horror stuff. Like, give me free hands and I’ll compose a set of songs, give out the stems, and let the cut editors do their stuff.

FW: And following on from that question, are there any projects you’d have liked to have scored, given the chance, and how would you have approached it differently to what we ended up with?

PA: About 80% of Finnish movies have embarrassing music. Sorry, but that is just troubling. The composers themselves are really gifted and compose beautiful music, but it’s either the director or the producers who pick up the wrong guys for the wrong projects. Also, a lot of production music is being used, which is just lazy in my opinion…a good example of “if you don’t care about your product”…

Having said that, I’d love to have composed Prometheus, as there was a very familiar and suitable amount of mystery and otherness connected with the ending’s horrific events. The movie field is well oversaturated, so I’m not exactly holding my breath for a call, let’s put it this way.

FW: Alan Wake 2 is incredibly tense and claustrophobic at times, with a great deal of that coming down to the soundtrack and score. What was the direction given by Sam Lake in regard to your final product, or were you given a general overview and just told to do as you wished?

PA: I mainly was given free hands to compose – only occasionally they wanted me to tighten the horror screw, and I usually replied by cranking it up to eleven and beyond, at times it felt like I’m not going to need any therapy ever, as all the black ghouls were let out and tamed with Alan Wake 2… heh, but in all seriousness, there’s the emotional range each human person has: you can draw from your fuel barrel, and yours only.

Claustrophobia fits exceptionally well here, as sometimes some sounds are very, very dry whereas, in contrast, I put a mile-long reverb just to emphasize how big a boogeyman can get in your head if you allow it to. That’s what Alan Wake was feeling all the time: he had to tame the monster within as well as others living in The Dark Place. A lot of horrific events grow from subjectivity and what exactly doesn’t happen, but might happen. The best horror doesn’t deliver, it merely suggests very, very, very heavily. Horror happens inside your brain.

If I die at 100 years old, I’d be very disappointed if I hadn’t changed from what I am now.

Sam’s coffee chats were an important tool, and many of them led to a few really great turns in the soundtrack, especially towards the end, where Alan Wake is once again driving back to Bright Falls after a sequence of horrific events leading to agent Casey conversion into a shadowy version of himself – and I felt, after the talk, that this is where Alan Wake encountered himself in a similar way to what happened in the original game where Wake decided to dive off the cliff to release his beloved wife. He gave all he had to get all he wanted. It’s a touching and sad moment, but in a very strange way, it also delivers the most hope the game allows.

Generally, our talks were reviews, where background stories and motivations were discussed and I was just happy to learn all that – a lot of my work is thinking and communication. Or, rather, communication and THEN thinking. And when the thinking cycle kicks in, it won’t leave you and stays with you no matter where you go and what you do – until music is let out. The release following the planning period is very rewarding, I might even consider myself a tad dependent.

FW: The Remedy Connected Universe is starting to come to fruition as we get further into it. Does the connectivity of the titles influence your composing, or do you try to keep them individual and unique?

PA: It does, very directly, and I try to support the main concept ideas within the RCU, as I’ve seen (and heard in my head) the birth of it – each game and their events are unique as are their concepts both graphically and musically, but there’s that ‘something’ that clings it all together. It may be me as a component, but I’m sure it’s more of a compositional and sound design aspect.

For instance, with Control I realized something could be so evil it both had its own “gravity” of sorts, as well as affecting the tuning. In Control, there were sections, where 15-tone and 12-tone scales were used at the same time, in Alan Wake 2, we bend the overtones and cause some instruments to ‘dive’ many, many octaves throughout their playing. I can tell it wasn’t exactly easy to keep the sound together whilst having it do a divebomb for 8 octaves.

I enjoyed hearing the lowest piano strings start to rattle – not real ones, but a library I had done in 192kHz; you can hear the highest overtones descend into one’s hearing range, and that’s very interesting, as you can still recognize the ‘essence’ or ‘imprint’ of the sound despite all the familiar frequencies are already gone. That’s how powerful the mental image of certain instruments is.

Unique is a powerful adjective, but it doesn’t have to be divisive, instead it’s inclusive, yet differing. There are regulations within a concept that include a certain set of instrumentation or a set of raw materials – or the material of raw material being recorded. In Control, the sounds originated from heavy wooden objects dragged on a concrete floor, in Alan Wake 2 they were – at least partially – metallic objects.

They all connect to the environment in one way or another, and in Alan Wake 2, The Dark Place environment is mostly urban, threatening, ominous cityscape of a largish city that’s not too far from nighttime New York… what sounds makes that scary? Amplify all that and turn them into instruments.

The same applied to The Oldest House in Control – it’s not duplicating the idea, it’s about using the same toolset to create something new, to keep it believable yet familiar in the strangest possible ways.

FW: Of all the work you’ve done for Remedy, what is your personal highlight?

PA: Alan Wake 2, easily. Just because of the amount of material and the range of the material – as well as the time span: one of the tracks one can hear is actually That Demo Track which I did back in 2004. It was never used, but I felt it would fit in the scene in the later stages of the game. There’s so much love put into the soundtrack of this game.

Now, having mentioned Alan Wake 2, I’m extremely proud of each project I’ve done with them, but I’m constantly trying to develop myself, to learn something from each project, to become a better weapon of choice. I don’t want to do the same thing all over again, say, to stick with one certain style that some people do – that’s okay for them, and totally fine – but I try to find a new angle for each project. If I die at 100 years old, I’d be very disappointed if I hadn’t changed from what I am now. It’d be me having wasted natural resources and everyone’s time by not evolving and not becoming a better human. At the same time, I’m trying to become a better musician and composer.

Alan Wake 2 has several really well-conceived moments in its concept, and I’ve found it resonates very well throughout the whole fanbase, I’m exceptionally happy about that. I know how I could, however, develop the concept even further, but time will tell if there ever will be any other Alan Wake games. DLCs will arrive, of that I’m sure, but they’ll be more or less in the same IP space conceptually.

FW: The Game Awards recently announced you and your score to be nominated in the Best Score and Music category. Congratulations! The competition is incredibly stacked this year, but if not yourself, who would you like to win the award and why?

PA: Oh gods, I’m not willing to choose just one, as they all are incredibly well-conceived entities and products. It’s impossible, actually. It’s a little like enjoying a fruit salad and announcing one day “I simply adore the pear here” whereas on another day it’d be “the pineapple is, by the way, the one that saves this portion…”

However, I’d love to right a wrong and give the award of best soundtrack 2014 to Alien: Isolation. Would that count?

FW: Lastly, what does the future hold for you? Any upcoming projects?

PA: Pop songwriting continues, and there will be a few interesting ones coming out. Since Alan Wake 2 I’ve already moved on to another project to continue RCU’s sonic development, but more news will come later… until then I’ll be just as zzzzip as I’m always. My Audio Director duties at the Finnish Broadcasting Company could be endangered due to my wanting to prioritize, and ‘quite a few’ audio branding – or sonic identity – projects are on my desk. The world needs good sound, good music, and interesting angles and perspectives, so I’m trying my best to offer help.

Having said that, I’m extremely good at scheduling, so… if you feel I could be of assistance, let me know.

Follow us for more entertainment coverage on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.